by Sivapriya Ambalavanan & Priyanka

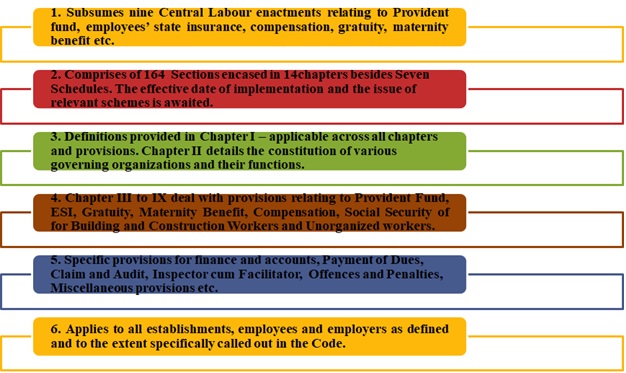

Introduction of the Code on Social Security in India was an essential step to reforming workplaces in the country. The Code on Social Security (COSS) 2020, which received the Presidential assent on 28 September 2020, subsumes nine regulations concerning social security, retirement and employee benefits. India’s labour ministry is currently in the process of finalizing the rules for the ‘Code on Social Security 2020’, which was passed by the parliament last September. The government has issued the Draft Rules on Social Security Code on November 13, 2020. The draft rules were put in the public domain for public feedback, and it is expected that this would be finalized in the near future. There are a few issues pertaining to this Code and Draft Rules presently under consideration, which we seek to discuss in the article.

This code aims to facilitate the implementation of Labour laws, reduce the multiplicity of definitions, streamline the numbers of authorities under various laws and ensure basic concepts of welfare and benefits to workers are preserved.

Another major objective of the code is to promote technology for ensuring compliance and enforcement of provisions thereunder are achieved with ease. This code aims to broaden the universal social security coverage by setting up a ‘Social Security Fund’ for 40 crore unorganized workers along with Gig and platform workers. Even the plantation workers will receive ESIC benefits alongside Gig and platform workers.

Analysis of the Act:

- Duality in the administration of social security schemes: Till now, respective state governments were responsible for the formulation and implementation of social security schemes for the unorganised sector workers. In the new COSS, this responsibility has been assumed by the Central Government.[2] Under Section 109(1), the Central Government shall frame and notify, from time to time, suitable welfare schemes for unorganised workers on matters relating to-(i) life and disability cover, (ii) health and maternity benefits, (iii) old age protection, (iv) education and (v) any other benefits as may be determined by the Central Government. Under Section 109(2), the government shall frame and notify, from time to time, suitable welfare schemes for unorganised workers, including schemes relating to- (i) provident fund, (ii) employment injury benefit, (iii) housing, (iv) educational schemes for children, (v) skill up-gradation of workers, (vi) funeral assistance and (vii) old age homes.[3] Thus, it seems that both the Central and State Governments will formulate schemes for unorganised sector workers in clearly demarcated areas. There would, therefore, be a dual authority from the attitude of a private unorganised sector worker.

- Provisions on Gig Workers and Platform Workers are “unclear” [Sec 109-114]: The COSS, 2020 introduces definitions for “Gig Worker” and “Platform Workers”. Gig Workers are workers outside the “traditional employer-employee relationship”. Platform Workers are those that are outside the “traditional employer-employee relationship” and access organisations or individuals through a web platform and supply services for payment. This Bill also contains provisions for the Unorganised Worker. An “Unorganised Worker” is defined as one who works in the Unorganised Sector and includes workers not covered by the Industrial Dispute Act, 1947 or other provisions of the Bill (such as Provident Fund or Gratuity). It also includes Self -employed workers. The Bill mandates different schemes for these categories of workers. However, there may be some overlap between their definitions. Consider the example of a “Driver” working for an App-Based Taxi Aggregator.[4] Here, there is no employee-employer relationship. For example, appointment letters aren’t issued, Social Security benefits are absent, work hours aren’t regulated by the employer, and therefore the driver may prefer to work for a competitor taxi aggregator. Therefore, the character of the work involved may lie outside the purview of a “traditional employer-employee relationship”, making him a “Gig Worker”. However, the driving force is in a position to pursue this job only through a web platform. This would meet the definition of a “Platform Workers” also. Such a driver can also be an “Unorganised Worker” as he could also be self-employed. With such overlap across definitions, it’s unclear how schemes specific to those categories of workers will apply.

- Provisions on Gratuity for fixed-term workers is unclear[ Sec 53 & Industrial Relations Code Clause 2(o)]: Under the COSS 2020, gratuity is payable if the employee has served a continuous period of five years. However, this point period won’t apply if the contract term of a fixed-term worker expires. The Bill further states that within the case of fixed-term employment, the employer can pay gratuity on a pro-rata basis i.e. proportionate to the fixed term period. However, the Industrial Relations Bill, 2020, while defining term workers, states such workers will be eligible for Gratuity only if they complete a one-year contract. Therefore, these two Bills contain different provisions on Gratuity for fixed-term workers and it is not clear whether a fixed-term employee with a contract of less than one year will be entitled to Gratuity under the COSS, 2020.

- Mandatory linking with AADHAR may violate Supreme Court judgment[Sec 113,142]: The COSS 2020 mandates an employee or a worker (including an unorganised worker) to provide his Aadhar number to receive social security benefits or to even avail services from a career centre.[5] This may violate the Supreme Court’s Puttaswamy -II judgement. In this judgment, the Court had ruled that the Aadhar card/ number may only be made mandatory for expenditure on a subsidy, benefit or service incurred from the Consolidated Fund of India. Applying this principle, the Court has struck down the mandatory linking of bank accounts with Aadhar. Since certain entitlements such as Gratuity and Provident Fund (PF) are funded by employers and employees and not by the Consolidated Fund of India, making Aadhar mandatory for availing such entitlements may violate the judgment.[6]

EPILOGUE

The government has failed to recognize that focusing on economic growth without redistribution of wealth leads to jobless growth and socially accountable prosperity. This leaves workers and communities poorer, insecure and vulnerable to economic shocks and vagaries of the labour market.[7]

Failing to address the issues of the workers threatens peace and harmony of the society and undermines the nation’s capability to improve the living and work conditions of the workers. Continuing to deny crores of workers their basic rights and entitlements will have serious implications for the sustainability of our growth model in the long term. Further, the present policy and process framework will need to be revisited in lines of the new code and technology interface should be appropriately built-in.